iTunes Podcast Recording

(Must download iTunes Podcast Application to listen on your mobile phone)

SERVICESPACE NEWSLINK

SERVICESPACE NEWS LINK

LATEST DEVELOPMENT– BOOK COVER FINISHED–ARTIST: HIRAM MELENDEZ

MOROCCO’S FORGOTTEN PROMISE:

THE PLIGHT OF STREET CHILDREN & ORPHANS

Honored to have my eyes as the muse in the corner of this socio-political art-piece. Check out his provocative and politically centered artwork atwww.hiramsart.com

Honored to have my eyes as the muse in the corner of this socio-political art-piece. Check out his provocative and politically centered artwork atwww.hiramsart.com

RESEARCH UPDATE

In the Fall of 2013 and the Spring of 2014, I had the great pleasure of collaborating with several Moroccan humanitarians that joined me in my quest for examining the plight of Moroccan street children and orphans. As strong advocates of women and children, we joined our public-spirited gifts to collaboratively research and share effective community-based and international humanitarian strategies. The goal is to publish research-proven strategies that make a significant impact for improving the quality of lives for these impoverished children. With the support of SOCIAL CHANGERS WITHOUT BORDERS, INC as well as several NGO’s and private sponsors, I will continue to examine the complex issues related to the abuse and tragic circumstances that Moroccan street children face as victims of child labor and sexual trafficking.

*****PUBLICATION EXCERPT*****

[Protected under copyright laws]

**********************************************************

MOROCCO’S FORGOTTEN PROMISE:

THE PLIGHT OF STREET CHILDREN & ORPHANS

Lead Advocacy Researcher

Dr. Vilma Caban-Vazquez, Ed.D

Introduction

As a humanitarian advocacy researcher, Dr. Caban-Vazquez’s vision was to further explore the international phenomena of the invisible and forgotten children of the world—abandoned orphans and street children. The issue of street children first came to her attention when she traveled as an educational reform delegate with a professional organization, The People to People Ambassador Program. It became quite apparent when she traveled to different parts of Egypt that there were many children in the streets either working or begging from tourists. Her observations helped her conclude that Egyptian street children were generally viewed as delinquents and a plague that should be treated with detention or jailing. Further examination revealed that Egyptian government legislation and policy towards street children was primarily punitive (Ali, 2006).

After witnessing a child getting physically abused in a market in Giza, this researcher-practitioner was emotionally drawn into this societal issue. She wondered why these children were unseen and did not have a voice. She wondered why it seemed like these forgotten souls were not valued and viewed as illegitimate members of their local society. After that unsettling experience, she longed to go back to an African and Arabic speaking country to explore this issue further.

In July 2013, Dr. Caban-Vazquez had the honor of serving as an international volunteer for a non-governmental organization (NGO) that offered various volunteering opportunities in developing nations throughout Asia, Africa, and South America. Her number one choice was to travel to Rabat, Morocco. It was the perfect fit! There she worked with the NGO’s international team of volunteers that offered educational and social service support to grassroots organizations directly helping orphans and street children.

In Rabat, Morocco this researcher’s heart was transformed by the tender moments she shared with the sick children that she served in a local hospital. Many of her fellow international volunteers were assigned to work at two local orphanages. In their home base, they shared their moving stories about serving these forgotten children. Furthermore, she was touched by the stories she heard from volunteers that tutored street children seeking educational experiences. While hearing their anecdotes, and observing how the compassionate international volunteers geared up for another day of dedicated service, Dr. Caban-Vazquez was inspired to formally launch an advocacy study centered on this societal problem. As a result, she reached out to several Moroccan citizens and compassionate souls who were eager to help her on her research journey. Through this unique research collaboration, they helped to raise awareness about Morocco’s societal problem of abandoned street children and orphans.

Definition of the Problem

In 2011, the Child Rights Governance Programme (2011) offered statistical findings that shed some light on the plight of Moroccan orphans and street children. Moreover, it captured the limited impact that recent initiatives are having on this marginalized population. Despite Morocco’s implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Children in 1993 and the New Code of Criminal Procedure in 2002, there are approximately 46,500 Moroccan children deprived of a home environment (Child Rights Governance Programme, 2011,p. 41). However, it seems that the true number of orphans is not fully and/or publicly disclosed. In various regional and national news press articles, the numbers are quoted as lower and closer to an estimated 30,000 abandoned children registered as orphans in the Kingdom of Morocco (World Health Organization, 2009).Likewise, it is quite challenging to find the exact figure of Moroccan street children as per documented by local and government officials. The State Secretariat for Children, Women, and Family acknowledged the difficulty of reporting the exact figures and attributes it to the children’s mobility as they travel within a city and/or region (UNICEF 2010). Despite several Moroccan initiatives to address this issue through public policy, the high rate of increased numbers of orphans and street children is a symptom of underlying societal issues related to this phenomenon (Moroccan American Center for Policy, 2012).

Rationale for Choosing the Problem

A broader examination of the body of professional literature revealed that in the past 20 years, the issue of Moroccan orphans and street children continues to grow exponentially. It is negatively impacting not only the lives of those forgotten children, but also the economic prosperity of this nation. A country’s future lies in its next generation of citizens. If a large portion of the citizenry is not positively active and serving as contributing members of that nation, the trajectory of that nation’s potential is highly compromised (United Nations Development Project, 2009).

Recent research findings by worldwide advocacy organizations report that the significant level of apathy and indifference directed towards street children and orphans, coupled with the sexual predatory and child labor risks that these children face, can further compromise the economic vitality of this nation (WHO, 2010; International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect-ISPCAN, 2006; Human Rights Watch, 2005; United Nations Human Rights Council, 2013). In summary, the rationale for conducting this humanitarian advocacy study is to develop a published resource that can provide greater insight for grassroots organizations serving this marginalized population.

Definition of Special Terms

The following definitions of key terms are associated with the local phenomenon of Moroccan abandoned orphans and street children. Child Maids/ Domestic Servants: According to the International Labour Organization (2013) child domestic work performed by ‘child maids’ or ‘domestic servants’ is a general reference for children that work in the domestic work sector. It is usually in the home of a third party or employer. The concept of a child maid encapsulates both permissible as well as impermissible situations wherein girls work on domestic duties for an employer outside of the home. This phenomenon is often hidden and hard to tackle because of its links to social and cultural patterns. In many countries, child domestic labor is not only socially and culturally acceptable, but viewed in a positive light. In fact, it is most often a protected and non-stigmatized form of work. It is commonly preferred more than other forms of employment – especially for girls. The perpetuation of traditional female roles and responsibilities (within and outside the household) and the perception of domestic service as part of a woman’s apprenticeship for adulthood and marriage, contribute to the persistence of child domestic work as a form of child labor.” (ILO, 2013).

NGO (Nongovernmental Organization): The United Nations expounds on the term NGO on it’s public information website entitled United Nations Rule of Law. It is defined as “…any non-profit, voluntary citizens’ group, which is organized on a local, national or international level. An NGO is task-oriented and driven by people with a common interest; NGOs perform a variety of service and humanitarian functions, bringing citizen concerns to Governments. They advocate and monitor policies and encourage political participation through provision of information. Some NGO’s are organized around specific issues, such as human rights, environment or health. They provide analysis and expertise; as well as serve as early warning mechanisms and help monitor and implement international agreements. Their relationship with offices and agencies of the United Nations system differs depending on their goals, their venue and the mandate of a particular institution” (2014).

Orphan: The United Nations defines an orphan as a child who has lost one or both parents. “By this definition there were over 132 million orphans in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean in 2005. This large figure represents not only children who have lost both parents, but also those who have lost a father with a surviving mother, or have lost their mother but have a surviving father.” (UNICEF, 2013).

Street Children: It is a marginalized population of children that live on the street, and they are not supported or protected by their families. The Consortium for Street Children (2013) notes that there lacks an internationally agreed upon definition of the term ‘street children’. However, UNICEF (2005) developed the earliest definitions and categories of street children:

- Children ‘of’ the street (street-living children), who sleep in public spaces, without their families;

- Children ‘on’ the street (street-working children), who work on the streets during the day and return to their family home to sleep;

- ‘Street-family children’ who live with their family on the street. Field research has helped to unveil an enormous variation in children’s experiences. There is a considerable overlap between these three groups of forgotten or abandoned children. For example:

- Some children live on the streets all the time;

- Others live on the streets only occasionally or seasonally;

- Many move between family member’s homes, the cruel streets, and a countless number of welfare shelters. Some street children are able to retain some strong links with their families, while others have broken or lost all contact.

- Likewise, ‘runaways’ in countries, such as the UK and USA, include children that may be described as ‘detached’, whereas those who live in underdeveloped countries would be considered ‘street children’ (CSC, 2013).

Significance of the Problem

As noted earlier, regardless of the enforcement and accountability measures established by international human rights organizations and government ministries, research findings suggest that many orphans and street children are still displaced and without adequate homes and protection. Consequently, this research project is designed to address this local problem. Our research team seeks to examine the leading causes that attribute to the high number of children living on the streets. Within the structure of a qualitative research study, the researchers seek to conduct an in-depth analysis by collecting and analyzing multiple forms of qualitative data centered on how local grassroots organization address the issues related to serving Moroccan orphans and street children.

Problem Statement

This qualitative advocacy study will explore issues related to the plight of Moroccan orphans and street children. After 20 years since the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children, humanitarian research findings show that the number of children affected by poverty and broken families continues to rise (World Bank, 2010a). Relevant empirical findings are needed to inform the decisions that shape policy and the implementation of child advocacy strategies.

Literature Review

The initial phase of this literature review revealed demographic findings that demonstrate a statistical trend and a strong correlation between the poverty level of a community with the high rate of abandoned orphans and street children in urban settings (World Bank, 2010b). Although protection laws have been slowly introduced to protect the rights of children, the process of enforcing these legal sanctions has been an arduous and quite complicated journey for NGO’s seeking to advocate and intervene to improve the quality of life for thousands of Moroccan orphans and street children. (Moroccan Children’s Trust, 2010). A rigorous review of research studies revealed two complex themes:

- The societal factors and stigmas that shape the course for the increased rate of abandoned children by single mothers.

- Several pressures for older children to flee from their families and face life in the streets of Moroccan urban centers.

A closer examination of research findings helped our research team gain a deeper understanding of the scale of this societal phenomenon. The sources for the literature review queries came from various peer-reviewed databases, which include ERIC, EBSCO, SAGE, and PROQUEST. The research team was able to access current and relevant full-texted copies of research findings related to Human Rights, International Human Rights initiatives, and Moroccan policy and mandates. Moreover, primary sources were available from various United Nations published reports across a broad span of human rights commissions and committees which included the United Nations International Emergency Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Project (UNDP), United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and other vital documents and publications from the United Nations Office of the High Commission of Human Rights (OHCHR). Secondary resources were used to further gauge general public opinions and perceptions regarding the status of Moroccan orphans and street children. Finally, numerous NGO executive reports were used to assess the aperture and depth of current intervention practices, and to gain insight on the implications for further research.

A closer examination of research findings helped our research team gain a deeper understanding of the scale of this societal phenomenon. The sources for the literature review queries came from various peer-reviewed databases, which include ERIC, EBSCO, SAGE, and PROQUEST. The research team was able to access current and relevant full-texted copies of research findings related to Human Rights, International Human Rights initiatives, and Moroccan policy and mandates. Moreover, primary sources were available from various United Nations published reports across a broad span of human rights commissions and committees which included the United Nations International Emergency Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Project (UNDP), United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and other vital documents and publications from the United Nations Office of the High Commission of Human Rights (OHCHR). Secondary resources were used to further gauge general public opinions and perceptions regarding the status of Moroccan orphans and street children. Finally, numerous NGO executive reports were used to assess the aperture and depth of current intervention practices, and to gain insight on the implications for further research.

Theoretical Framework

This qualitative research team will conduct a phenomenological research study in which they will describe the “essence of human experiences concerning a phenomenon, as described by the participants of the study” (Creswell, 2003, p.15). The theoretical framework for this inquiry is based on a constructivist approach, wherein the researchers will position themselves to collect the participants’ experiences and understanding regarding their plight as street children and orphans in Morocco. They will study those participants’ constructs within the context of different situations and circumstances. The researchers will examine the different forces that shape their paths as they contend with life on the street, an orphanage, or transitional setting.

Using a variety of qualitative data collection methods, the researchers will analyze and make interpretations based on the findings. Using an advocacy/participatory approach, the researcher-practitioners will engage the study participants as active collaborators to help inform and advance an action agenda for change (Creswell, 2003, p.11). As a result, this phenomenological research study will help the research team develop a broader understanding of the many interrelated issues that shape the plight of many Moroccan orphans and street children.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Caban-Vazquez served as an executive board member and advocacy researcher for a grassroots community organization, Social Changers without Borders, Inc. Vilma feels honored to work with this organization’s research scholars, which include Walden University Alumni, faculty, and students promoting positive social change around the world. In July 2013, Dr. Caban-Vazquez traveled as an international volunteer for Cross-Cultural Solutions, which is a non-profit organization serving abandoned street children and orphans in Rabat, Morocco. Click here to learn more about her research journey: DoctoraVazquez’sBio

MORROCAN RESEARCH STUDY SUPPORTERS

ARTIST’S WEBSITE: http://www.hiramsart.com/ INTERVIEW WITH THE ARTIST: http://www.visionesculturales.com/video-archivesinterviews.html Special thanks to the founders of Visiones Culturales (Yolanda Luz Rodriguez & Margie Soto) for their tireless efforts in organizing the Latino Art Exhibit at the Andrew Freeman Mansion in New York City. It was the perfect cultural forum! WEBSITE: www.visionesculturales.com or https://www.facebook.com/VisionesCulturales

ARTIST’S WEBSITE: http://www.hiramsart.com/ INTERVIEW WITH THE ARTIST: http://www.visionesculturales.com/video-archivesinterviews.html Special thanks to the founders of Visiones Culturales (Yolanda Luz Rodriguez & Margie Soto) for their tireless efforts in organizing the Latino Art Exhibit at the Andrew Freeman Mansion in New York City. It was the perfect cultural forum! WEBSITE: www.visionesculturales.com or https://www.facebook.com/VisionesCulturales

“FORGOTTEN PROMISE” By Hiram Melendez

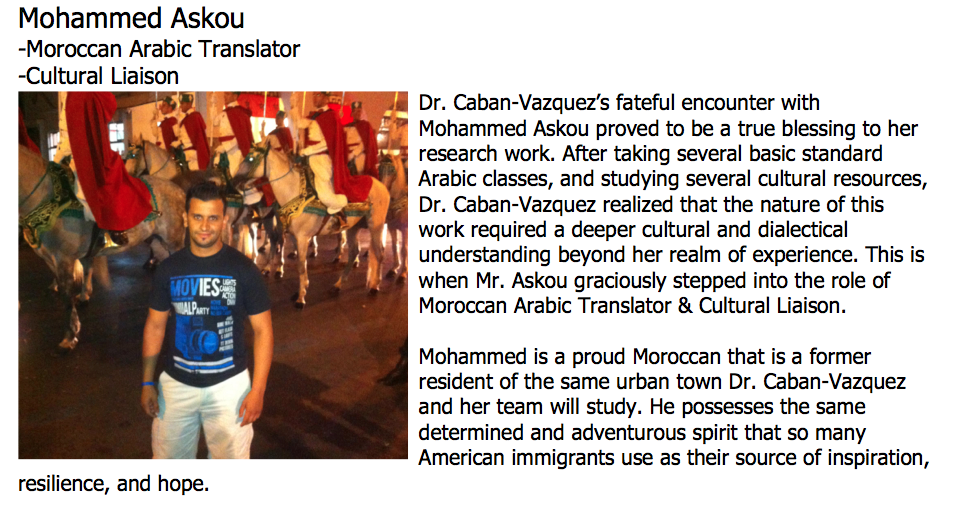

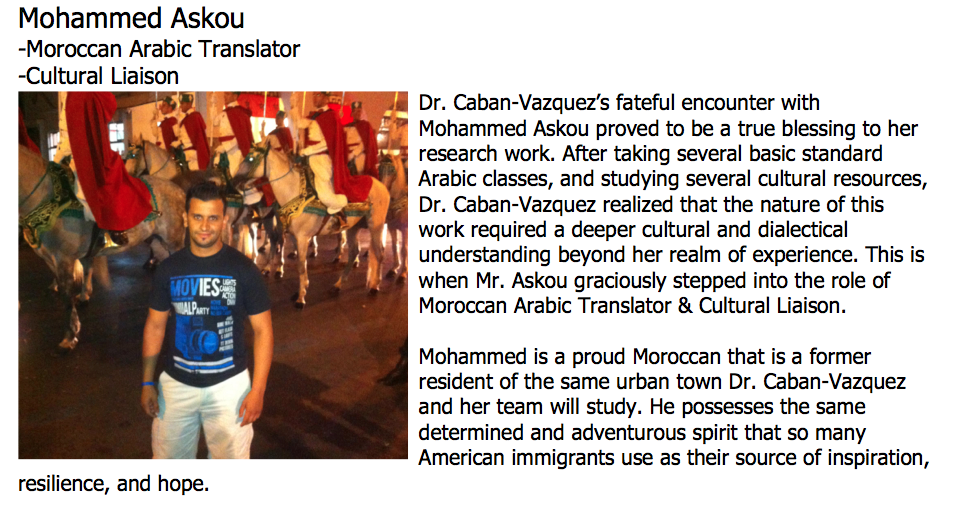

Mohammed takes great pride in sharing about his humble journey. He is the proud son of his Moroccan parents and this truly helps him appreciate the simple pleasures of life. Although he grew up poor, he describes his Moroccan life with his family in Salé as a blessed life. However, there was a calling on Mohammed’s heart, to reach outside of Morocco and find a way to improve the quality of life for his parents’ and siblings. At this point in Mohammed’s journey, he deals with the emotional struggle of knowing his father continues to be very ill. However, with Mohammed’s work here, the family is able to pay for essential and expensive medical treatment and medication. Ultimately, this is the reason why Mohammed diligently works extended hours. Although life in the United States has not been easy, Mohammed remains steadfast and positive. In those still moments when he misses his family, Mohammed leans on the cultural links and traditions that remind him of home. Mohammed looks forward to doing all he can to support Dr. Caban-Vazquez’s research efforts because he feels that it is a way to give back to his beautiful Moroccan community.

Mohammed takes great pride in sharing about his humble journey. He is the proud son of his Moroccan parents and this truly helps him appreciate the simple pleasures of life. Although he grew up poor, he describes his Moroccan life with his family in Salé as a blessed life. However, there was a calling on Mohammed’s heart, to reach outside of Morocco and find a way to improve the quality of life for his parents’ and siblings. At this point in Mohammed’s journey, he deals with the emotional struggle of knowing his father continues to be very ill. However, with Mohammed’s work here, the family is able to pay for essential and expensive medical treatment and medication. Ultimately, this is the reason why Mohammed diligently works extended hours. Although life in the United States has not been easy, Mohammed remains steadfast and positive. In those still moments when he misses his family, Mohammed leans on the cultural links and traditions that remind him of home. Mohammed looks forward to doing all he can to support Dr. Caban-Vazquez’s research efforts because he feels that it is a way to give back to his beautiful Moroccan community.

REFERENCES:

Consortium for Street Children. (2010). Frequently Asked Questions: “Who is a Street Child?”. Retrieved from

http://www.streetchildren.org.uk/ content.asp?pageID=31#streetchild

Child Rights Governance Programme. (2011). Country Profile of Morocco: A review of the implementation of the UN Convention on the rights of the child. The Manara Network & International Bureau for Children’s Rights. Save the Children Sweden, Regional Office. Retrieved from

http://resourcecentre. savethechildren.se/library/country-profile-morocco-review-implementation-un-convention-rights-child

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Freire, P, (1997 ), Pedagogy of the Oppressed.(rev.ed) New York, NY, Continuum. In Mefalopulos P. & Tufte T (2009), Participatory Communication. A Practical Guide: Washington DC, The World Bank p 7

International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. (2006).

Street Children in Morocco: Analysis of the Situation. ISPCAN Newsletter: The Link. Vol. 15. No. 3. Chicago, IL. Retrieved from

http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.ispcan.org /resource/resmgr/link/link15.3.english.pdf

United Nations Human Rights Council. (2013). Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Children Working and/or Living on the Street. Office of the High Commission of Human Rights. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Children/Study/OHCHRBrochureStreetChildren.pdf

World Health Organization. (2009). Country cooperation strategy for WHO and Morocco 2008-2013. Retrieved from

http://www.who.int/countryfocus/ cooperation_strategy/ccs_mar_en.pdf.

SO HUMBLED BY THIS ARTICLE: THANK YOU SO MUCH!!!!

SO HUMBLED BY THIS ARTICLE: THANK YOU SO MUCH!!!!